Secure care for children at risk – let’s start the conversation

Aug 2025

Written by Kate Crowe

Not many people know what secure care is and are surprised to hear that it exists in many states and territories in Australia. It’s anonymity in a way protects children and young people. It protects them from stigma, and sometimes quite literally from people harming them – in non-descript houses with hidden addresses. Anonymity also stops secure care from being politicised, potentially like youth justice, susceptible to reactionary, media driven policy not evidenced-based decision making.

Unfortunately, however, secure care’s anonymity has also stifled the development of an evidence basis to inform models of care, and the question remains as to whether it is more (or less) effective than non-secure, community-based interventions. It has also stifled public discourse on the question as to whether we, in Australia, would like to have secure care and if so, in what form and for whom?

What is secure care?

This question could arguably be where the confusion and ambiguity surrounding secure care begins. There is no internationally agreed upon definition of secure care. It can be referred to as secure accommodation, secure home, secure care estates, secure welfare services, secure care service, safe care, secure residential care, special care, closed care, closed accommodation, intensive therapy place or a secure residence…. just to name a few.

These are terms used to describe a locked institution in the welfare sector whose objective is to care and protect children, often with child protection involvement, who are admitted due to significant risk of harm to themselves and/or others. Children and young people admitted to secure care are often exposed to restrictive measures including seclusion and physical restraint.

The vast majority of children admitted to secure care are children have child protection involvement and are often residing in residential care. Reasons for admission generally include a combination of the following: substance misuse, missing from care, mental health issues (self-harm/suicide ideation), violent behaviours and sexual exploitation.

Children are generally admitted between the ages of 12 and 18 years however there are often exceptions at either end of the age range. These institutions are residential care houses/facilities which can house one or more children. Generally, they are small scale (e.g. 4-10 children), however they can be large institutions (e.g. 40-60 children). There is a trend internationally of moving to small scale facilities. A current challenge is the isolation of children in ‘seperate care’.

There is debate as to whether ‘separate care’ is a form of secure care. Separate care is considered to be a locked residential care response for a single child. ‘Separate care’ can also be referred to as a separate institution, a Deprivation of Liberty Order, home-based deprivation of liberty, a locked placement, or a ‘boutique placement’. There is often even less transparency, oversight and regulation around what this form of secure care.

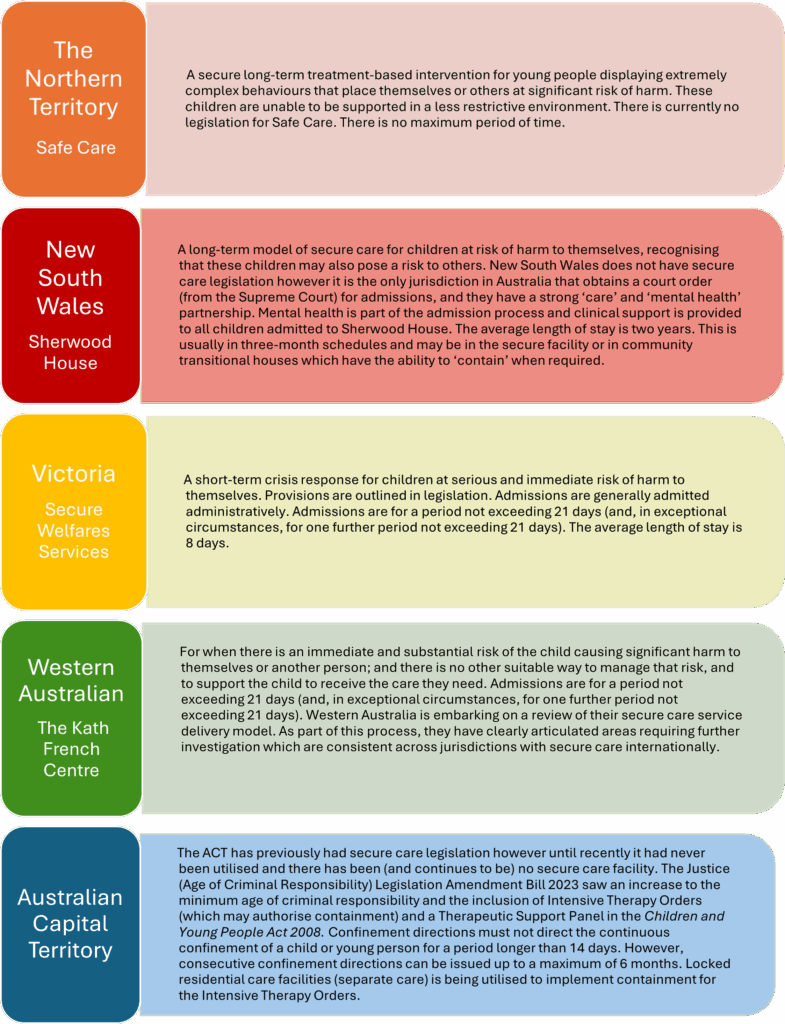

What secure care exists in Australia?

Below is an overview of secure care interventions in Australia:

Tasmania, South Australia and Queensland do not have secure care and utilise therapeutic residential care and behaviour support plans as alternatives to secure care (Crowe, 2024). No research has been conducted comparing the outcomes of children in states and territories with and without secure care.

Why is secure care such a hidden practice?

The cultural silence surrounding secure care is arguable perpetuated by a lack of publicly available data. Secure care admissions are not included in the Australian Institute of Health Wellbeing Child Protection Report. The Australia Bureau of Statistics publishes data by states and territories on how many children are sentenced to custody in correctional institutions in Australia. The Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023, however, does not do the same for the number of admissions into in locked child protection institutions in Australia.

So why is there such a lack of transparency in Australia? My theory is that it is due to a combination of the below reasons:

- Australia often doesn’t have specific ‘secure care orders’; as such there is an absence of reporting through court annual reports or the equivalent of sentencing advisory councils which publish sentencing outcomes.

- Not only do secure care interventions in states and territories go by different names and are not called ‘secure care’ but there is also significant variation in the design of secure care, and the use of secure care legislation (when in place), policy and practice.

- It is a highly sensitive service provided by government and is nested in the child protection sector. It relates to a small number of children experiencing extremely personal trauma.

- There are no national oversight mechanisms or standards for secure care in Australia.

Pathway to evidence-based models of care?

Later this year, a panel session hosted by the Australian Childhood Foundation, will start a public conversation about secure care in Australia. Starting a dialogue will hopefully pave a pathway for further collaborations and research into secure care, so we can ensure that our response to Australia’s children experiencing the most significant of harms is the most effective it can be. I look forward to sharing with you in this conversation.

Author biography

Kate Crowe holds a longstanding commitment to improving interventions and safeguards for children and young people experiencing serious vulnerability. For the past 20 years Kate has worked in the Commonwealth and State Government, leading reforms in youth justice, alternative care (out-of-home care), and secure care.

Kate was awarded a 2022 Churchill Fellowship to study effective alternatives to secure care for high-risk children and young people in Scotland, the Netherlands, Canada, and Hawaii. In 2023, Kate was awarded a Creswick Fellowship to investigate the position and design of secure care when jurisdictions raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility in Scotland, Finland, and Iceland. She has recently been appointed an Honorary Fellow at the University of Melbourne. Her publications include:

- Crowe, K. (2016). Secure Welfare Services: Risk, Security and Rights of Vulnerable Young People in Victoria, Australia. Youth Justice, 16(3), 263-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225416639396

- Crowe, K. (2024). Community-Based Alternatives to Secure Care for Seriously At-Risk Children and Young People: Learning from Scotland, The Netherlands, Canada and Hawaii. Youth, 4(3), 1168-1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030073

Kate is a member of the Group of International Researchers in Adolescent Forensic Research (GIRAF) and co-leads the ‘baby GIRAF’ sub-group on alternatives to secure care.